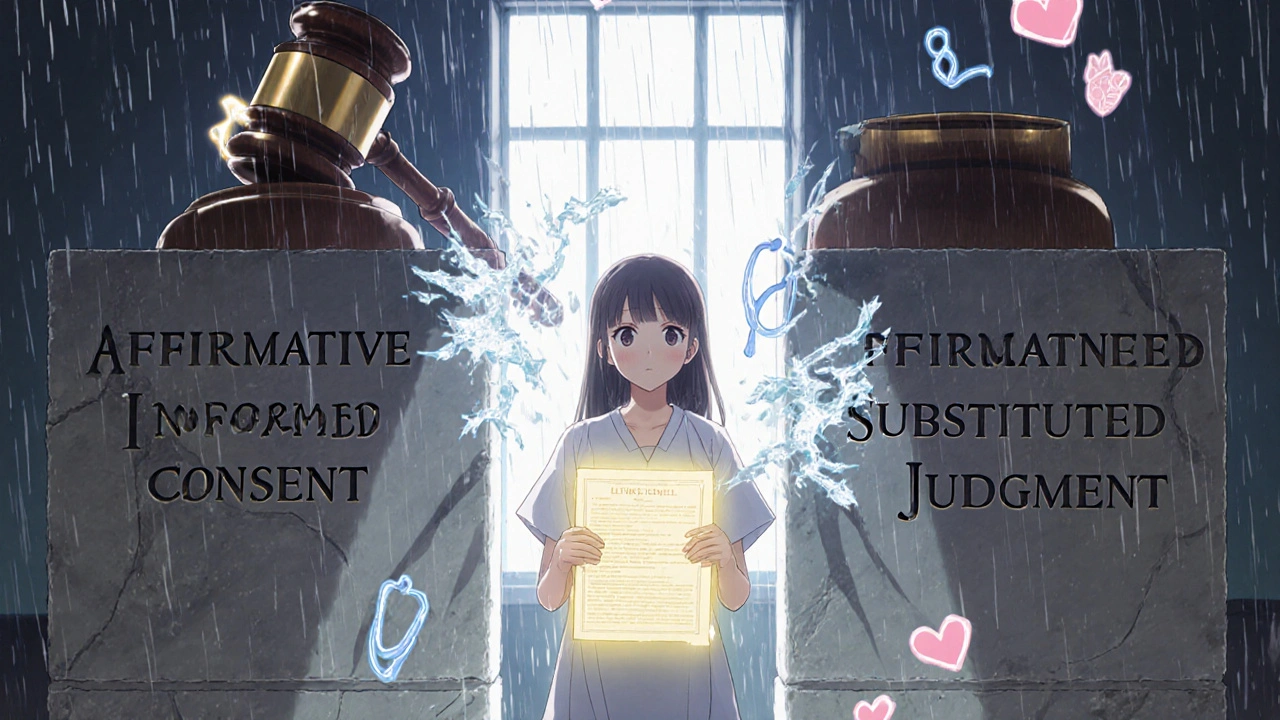

There’s a big mix-up going on-and it’s costing people time, clarity, and sometimes even care. You’ve probably heard the term affirmative consent in the news, especially around campus policies or sexual assault prevention. But when someone says, "What about affirmative consent for medical substitution?"-they’re mixing two completely different legal worlds. And that confusion can lead to dangerous misunderstandings in hospitals, clinics, and homes.

What affirmative consent actually means

Affirmative consent laws were never designed for medicine. They were created to change how we talk about sex. In 2014, California passed Senate Bill 967, which became the first state law to require that consent for sexual activity must be affirmative: clear, voluntary, ongoing, and reversible. It’s not enough to say "no"-you need a clear "yes." This became known as the "yes means yes" standard. Since then, 13 U.S. states have adopted similar rules, mostly for college campuses and sexual misconduct cases.These laws focus on one thing: preventing sexual violence by making sure everyone involved is actively agreeing, not just passively not objecting. The FRIES model-Freely given, Reversible, Informed, Enthusiastic, Specific-is used in training across universities and health centers. But none of this applies to medical decisions.

Medical consent is a different system entirely

When you walk into a doctor’s office, the law doesn’t ask if you’re enthusiastically saying yes to a blood test. It asks: Do you understand what’s happening, and are you choosing it freely? That’s informed consent.Informed consent has been around for over a century. It started with a 1914 court case, Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital, where a patient was operated on without permission. The judge ruled: "Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body." That’s the foundation of modern medical ethics.

Today, doctors must explain:

- What the condition is

- Why the treatment is recommended

- What the risks and benefits are

- What other options exist

- What happens if you do nothing

- Whether you’re able to make this decision

You sign a form not because you shouted "yes!"-but because you’ve been given the facts and made a choice. That’s it. No ongoing verbal check-ins. No need to be "enthusiastic." Just informed and willing.

What happens when a patient can’t decide?

Now, what if someone can’t give informed consent? Maybe they’re unconscious after an accident. Maybe they have advanced dementia. That’s where the real confusion kicks in. People start asking: "Can we use affirmative consent here?" The answer is no-and here’s why.Medical law has a clear path for these situations: substituted judgment and best interest standard.

If the patient made an advance directive-a living will or healthcare power of attorney-that’s what the doctor follows. If not, a legally appointed surrogate (like a spouse, adult child, or court-designated guardian) steps in. Their job isn’t to guess what they’d want. It’s to ask: What would this patient have chosen, if they could speak?

For example: A 72-year-old woman with Alzheimer’s has never wanted to be kept alive on machines. Her daughter, acting as surrogate, refuses a ventilator-even though it might extend life-because she knows her mother’s values. That’s substituted judgment. The daughter isn’t saying "I think this is best." She’s saying, "This is what Mom would have wanted."

California’s Health and Safety Code Section 7185 makes this official. Other states have similar rules. The American Medical Association’s 2023 guidelines say plainly: Do not apply sexual consent standards to medical decisions. The two systems serve different purposes. One prevents violence. The other protects autonomy.

Why does this mix-up matter?

Confusing these two systems isn’t just inaccurate-it’s harmful. Here’s what happens when people think "affirmative consent" applies to medicine:- A nurse delays a life-saving procedure because they’re waiting for a patient to say "yes" out loud-when the patient is unconscious.

- A family member refuses to sign for surgery because they don’t feel "enthusiastic" enough, even though the patient had a clear living will.

- A doctor avoids discussing end-of-life options because they’re afraid of being accused of not getting "affirmative" approval.

At the University of Colorado Denver, a 2023 survey found that 78% of undergraduates thought affirmative consent rules applied to medical care. That’s not just a misunderstanding-it’s a public health risk.

Even medical students get it wrong. On Reddit’s r/medschool, a thread from January 2023 asking "Is affirmative consent used in hospitals?" got over 1,200 upvotes after one student replied: "No. That’s for sexual misconduct cases. Medical consent is about understanding, not constant verbal confirmation."

Real-world examples of what works

Let’s look at two real situations.Case 1: Emergency surgery

A man is brought in after a car crash. He’s unconscious. His wife is there. The doctors explain: "He needs immediate surgery to stop internal bleeding. Without it, he’ll likely die. The surgery has risks, but they’re lower than not doing it." The wife says, "Do it. He’d want this." The team proceeds. No form is signed on the spot-time doesn’t allow it. But they document the conversation. This is legal. This is ethical. And it’s not affirmative consent. It’s substituted judgment.

Case 2: Teenager seeking birth control

In California, a 15-year-old can legally consent to treatment for STDs, HIV, or pregnancy-related care-even without parental permission. The doctor doesn’t ask if they’re "enthusiastic" about the pill. They ask: "Do you understand how it works? What are the side effects? Are you sure you want this?" The teen says yes. The doctor writes it down. That’s informed consent. Not affirmative. Not sexual. Just medical.

What’s changing? What’s not

Some people hope that the momentum behind affirmative consent laws will spread to medicine. But legal experts say that’s not happening-and won’t.In 2022, California passed AB569, which updated sexual consent rules. It didn’t touch medical laws. In 2023, the federal CARE Act focused on improving advance directives for elderly patients. No mention of "affirmative consent." The California Supreme Court even ruled in Doe v. Smith (Case No. S278143) that affirmative consent laws apply only to sexual misconduct cases under Title IX and education codes.

The American Medical Association, the Federation of State Medical Boards, and bioethicists like Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel all agree: medical consent and sexual consent are not interchangeable. Trying to merge them would create chaos in emergency rooms, slow down care, and confuse patients and families.

What you should remember

If you’re making a medical decision for yourself or someone else:- Don’t wait for enthusiastic "yeses." Look for understanding, not excitement.

- Don’t assume a loved one’s silence means "no." If they’ve left a living will or named a proxy, that’s your guide.

- Don’t confuse campus policies with hospital rules. They’re different systems, different laws, different goals.

- Ask for clarification. If a doctor says "we need consent," ask: "Do you mean informed consent? Is there a form? What are the options?"

Medical care doesn’t need to be loud. It needs to be clear. And the law agrees.

Do affirmative consent laws apply to medical procedures?

No. Affirmative consent laws are designed for sexual activity and apply to campus policies and criminal law, not medical treatment. Medical decisions use informed consent, which requires understanding and voluntary agreement-not ongoing verbal affirmation.

What is substituted judgment in medical decisions?

Substituted judgment is a legal standard used when a patient can’t make their own medical decisions. A surrogate, like a family member or court-appointed guardian, must decide based on what the patient would have chosen, based on their known values, beliefs, and past statements-not what the surrogate thinks is best.

Can a minor give consent for medical treatment?

Yes, in many cases. In California, minors as young as 12 can consent to treatment for sexually transmitted infections, HIV, substance abuse, and reproductive health. This is part of informed consent law, not affirmative consent. The key is whether the minor understands the treatment-not their age alone.

What’s the difference between informed consent and affirmative consent?

Informed consent is about understanding: the patient must know the risks, benefits, and alternatives before agreeing to treatment. Affirmative consent is about active, ongoing verbal or physical agreement during sexual activity. One protects medical autonomy; the other prevents sexual violence. They’re not interchangeable.

If a patient is unconscious, can doctors proceed without family approval?

In true emergencies where delay would cause serious harm or death, doctors can proceed without consent under the "emergency exception." This is a well-established legal principle. Once the crisis is over, they’ll seek consent or contact a surrogate. But they don’t wait for a "yes" from family if the patient’s life is at risk.

Why do people confuse these two types of consent?

The word "consent" is used in both contexts, and both involve personal rights. But the rules are built on different laws, different histories, and different goals. Media coverage often doesn’t explain the difference, and students-especially in health fields-are frequently taught about one without the other. This leads to widespread misunderstanding.

What to do next

If you want to make sure your medical wishes are respected:- Write an advance healthcare directive

- Name a trusted person as your healthcare proxy

- Have honest conversations with family about your values

- Keep a copy where it’s easy to find

And if someone tells you medical consent requires "affirmative" approval? Politely correct them. The law doesn’t work that way-and your care shouldn’t depend on a misunderstanding.