Before antiretroviral therapy became the standard, HIV was a death sentence. In the mid-1980s, people diagnosed with AIDS had less than a year to live. Then came zidovudine-also known as AZT-the first drug ever approved to treat HIV. It wasn’t a cure. But for the first time, it gave patients a fighting chance. And behind that breakthrough was a story not just of science, but of pressure, profit, and the powerful role pharmaceutical companies played in shaping the course of a global epidemic.

The birth of zidovudine

Zidovudine wasn’t invented to fight HIV. It was developed in 1964 by Jerome Horwitz at the Michigan Cancer Foundation as a potential cancer treatment. It failed. The drug sat in a lab for nearly two decades, forgotten. Then, in the early 1980s, scientists began to understand that HIV was a retrovirus-a type of virus that inserts its genetic code into human cells. That’s when researchers realized: drugs designed to block reverse transcriptase, the enzyme retroviruses use to replicate, might stop HIV in its tracks.

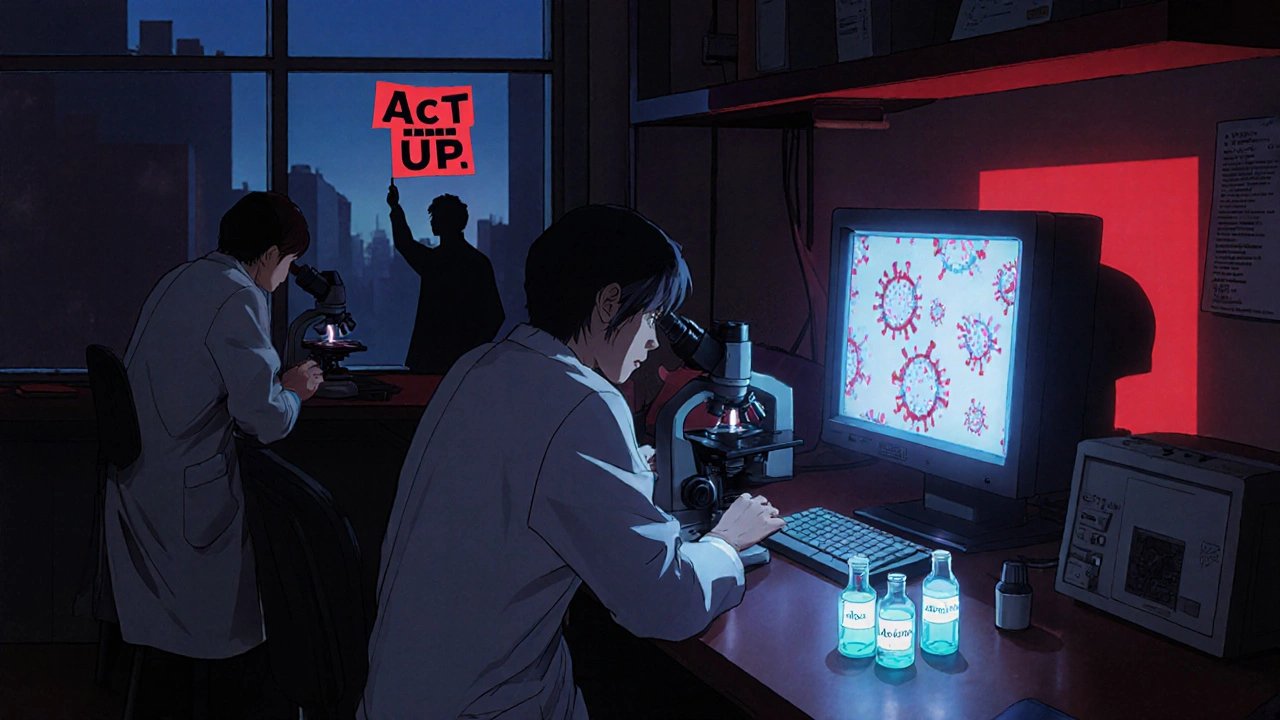

By 1985, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) tested zidovudine against HIV in lab cultures. The results were clear: it blocked the virus. Within months, the drug moved to human trials. The urgency was staggering. By 1986, over 20,000 Americans had died of AIDS. Families were burying children. Hospitals were overflowing. Activists stormed FDA offices. The public demanded action.

Fast-tracked approval and the role of Burroughs Wellcome

The company that held the patent for zidovudine was Burroughs Wellcome, now part of GSK. They were a respected, conservative pharmaceutical firm. But the crisis forced them into the spotlight. In 1986, they applied for FDA approval. The agency responded with unprecedented speed. In March 1987, zidovudine became the first drug approved specifically for HIV treatment-just 25 months after the first human trial began.

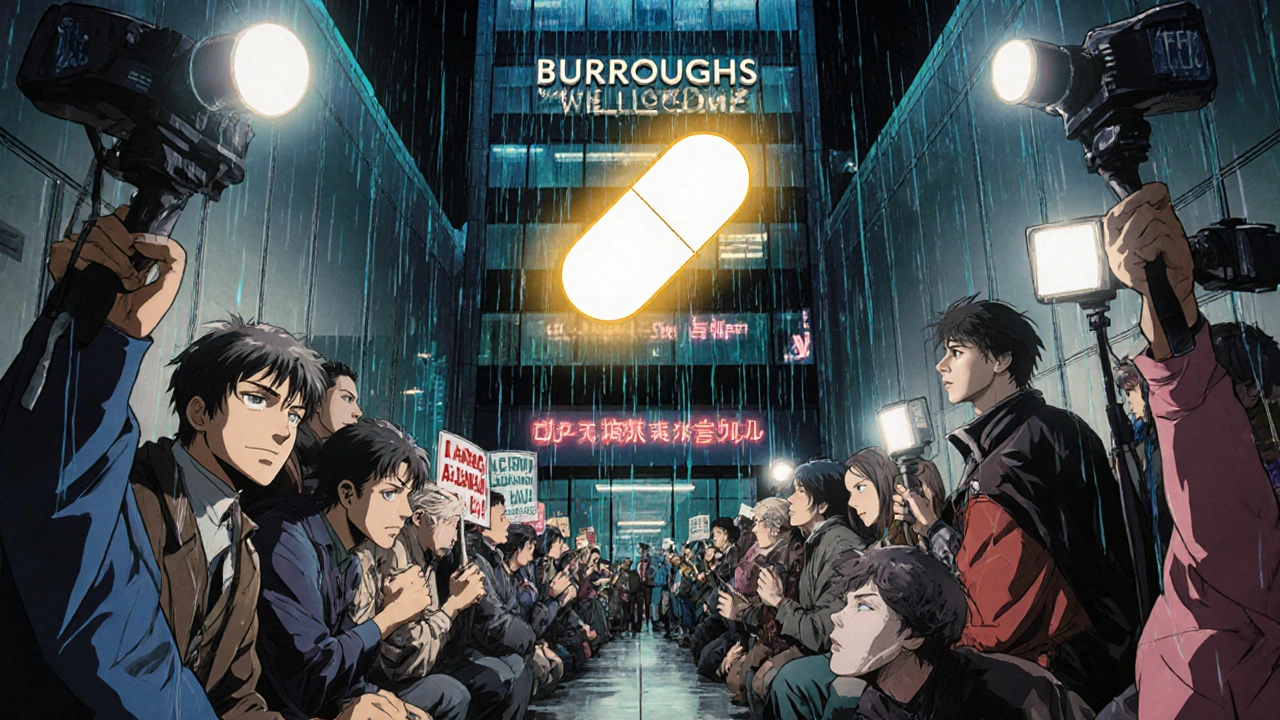

The approval was hailed as a medical miracle. But the price tag told another story. Burroughs Wellcome set the annual cost at $10,000 per patient-more than the median U.S. household income at the time. In a single year, a patient could spend more on AZT than on their mortgage. Critics called it price gouging. Activists organized protests outside the company’s headquarters. One group, ACT UP, famously shut down the FDA with a die-in, holding signs that read, “YOUR DRUGS ARE KILLING US.”

What many didn’t realize was that Burroughs Wellcome had invested $100 million in development, much of it funded by public grants. Still, the public saw a profit-driven company charging thousands for a drug that saved lives. The backlash wasn’t just moral-it was political. By 1988, pressure forced the company to lower the price to $6,400. Later, they offered discounts to low-income patients and governments. But the damage was done: the public now saw pharmaceutical companies as gatekeepers of life and death.

Zidovudine’s limitations and the rise of combination therapy

Zidovudine worked-but not for long. Many patients developed resistance within months. Side effects were brutal: severe anemia, nausea, muscle wasting. Some patients stopped taking it because they felt worse than before. By 1990, it was clear: monotherapy with AZT wasn’t enough.

The real turning point came in 1996, when scientists discovered that combining three drugs-zidovudine with two others-could suppress HIV to undetectable levels. This was the birth of HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy). Suddenly, HIV stopped being a death sentence. People started living decades with the virus. Zidovudine was no longer the star. But it was the foundation.

Today, zidovudine is rarely used alone. It’s mostly found in fixed-dose combinations like Combivir (AZT + lamivudine) or Trizivir (AZT + lamivudine + abacavir). These are used in resource-limited settings where newer drugs are too expensive. In sub-Saharan Africa, zidovudine is still given to pregnant women to prevent mother-to-child transmission. It’s not glamorous. But it’s effective. And it’s cheap-less than $50 a year per patient in generic form.

How pharmaceutical companies changed the game

Zidovudine’s story didn’t just change HIV treatment-it changed how the world sees drug companies. Before AZT, pharmaceutical firms were seen as quiet innovators. After AZT, they became symbols of corporate power. The controversy forced the industry to adapt.

Companies began investing more in HIV research. By the late 1990s, dozens of new antiretrovirals were in development. Competition drove prices down. Generic manufacturers in India and Brazil began producing affordable versions, undercutting Western firms. In 2001, the WHO listed zidovudine as an essential medicine. That meant low-income countries could legally import generics without permission from the patent holder.

Today, over 20 generic manufacturers produce zidovudine. The price has dropped more than 95% since the 1990s. What was once a luxury for the wealthy is now a lifeline for millions in the Global South. That shift didn’t happen because companies became altruistic. It happened because activists, governments, and generic drugmakers forced them to.

The legacy of zidovudine

Zidovudine is no longer the frontline treatment. Newer drugs like tenofovir and dolutegravir are more effective, with fewer side effects. But without AZT, those drugs might never have been developed. It was the first domino to fall. It proved HIV could be treated. It showed that patients could survive longer. And it proved that public pressure could change corporate behavior.

The pharmaceutical industry didn’t invent the cure for HIV. But they were the ones who turned a failed cancer drug into the first weapon against the virus. They made it available-too slowly, too expensively, too reluctantly. But they made it available.

Today, 39 million people live with HIV. Over 29 million are on treatment. That’s thanks to the science of zidovudine-and the pressure that forced companies to let go of their grip on it. The story of AZT isn’t just about a molecule. It’s about power, protest, and the messy, imperfect path to saving lives.

Is zidovudine still used today?

Yes, but rarely as a standalone treatment. Zidovudine is now mostly used in combination with other antiretrovirals, especially in low-income countries. It’s still a key part of preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission during pregnancy and delivery. Generic versions make it affordable for public health programs in Africa and Asia.

Why was zidovudine so expensive at first?

Burroughs Wellcome priced AZT at $10,000 per year in 1987 because they held the patent and faced no competition. They argued the cost covered R&D expenses, including $100 million in funding, much of it from public grants. But with no other HIV drugs on the market, patients had no choice. Public outrage and protests forced the company to lower the price within a year.

Did zidovudine really work?

Yes-but with limits. Early trials showed AZT reduced viral load and extended survival by about 10 months. It improved quality of life for many. But resistance developed quickly, and side effects like anemia and fatigue were common. It was never meant to be a long-term solution. Its real value was proving that HIV could be suppressed with drugs, paving the way for combination therapy.

How did activism change HIV drug access?

Activist groups like ACT UP forced governments and drug companies to act. Protests, lawsuits, and public shaming led to faster FDA approvals, price cuts, and eventually, the right for countries to produce generic versions of patented drugs. In 2001, the WTO allowed compulsory licensing for HIV medicines, letting poor nations import cheaper generics. That move saved millions of lives.

What’s the difference between zidovudine and modern HIV drugs?

Modern drugs like dolutegravir or tenofovir are more potent, have fewer side effects, and require only one pill per day. They also have a higher barrier to resistance-meaning the virus is less likely to become immune. Zidovudine requires more frequent dosing and causes more toxicity. But it’s still useful where cost matters most: a year’s supply of generic AZT costs under $50, while newer drugs can cost hundreds.