Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only cost 10% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s the math behind affordable healthcare. But behind those numbers is a quiet crisis: many generic manufacturers are losing money. Some are barely breaking even. Others are shutting down production lines because they can’t afford to keep making essential medicines. How did we get here? And more importantly-how can this system survive?

The Price Collapse of Commodity Generics

Twenty years ago, making a generic version of a common antibiotic or blood pressure pill could earn a company a 50-60% gross margin. Today? Many are lucky to hit 20%. In some cases, margins have sunk below 10%. Why? Too many manufacturers, too few customers with buying power.The U.S. pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) system drives this. PBMs negotiate bulk discounts for insurers, but they don’t pass savings on to manufacturers. Instead, they pit generic makers against each other in a race to the bottom. One company lowers its price by 5 cents. Another drops 10. Soon, no one’s making a profit. The FDA approved over 1,600 generic drugs in 2024 alone. Each one adds another player to an already overcrowded market.

Take the case of injectable epinephrine. After the brand patent expired, over 20 companies entered the market. The price per auto-injector dropped from $1,200 to $45. That’s great for patients. But for the manufacturer? They’re now losing money on every unit sold. Some stopped production. Others moved to other countries. And now, in some U.S. regions, there are shortages. That’s not a supply chain glitch-it’s a business model failure.

The Three Paths to Survival

Not all generic manufacturers are stuck in the same trap. Three distinct business models are emerging-and only two of them are still profitable.Model 1: Commodity Generics - This is the old way. Make simple pills. Sell them cheap. Hope volume makes up for thin margins. It’s collapsing. Companies still trying this model are bleeding cash. Teva, once the world’s largest generic maker, reported a -4.6% profit margin in 2025. That’s a $174 million loss on $3.8 billion in sales. This path is no longer sustainable.

Model 2: Complex Generics - These aren’t your run-of-the-mill tablets. They’re inhalers, injectables, topical creams, or combination drugs that are hard to replicate. Think of a drug that needs precise particle size control, or one that requires special delivery systems to work in the gut. The FDA approval process for these takes longer, costs more, and has fewer competitors. That’s the sweet spot. Companies like Viatris and Teva are pouring money into this. Teva spent $998 million on R&D in 2024, mostly on complex generics for neurological and autoimmune diseases. These products can carry 40-60% margins. The catch? You need deep technical expertise. Not every factory can do it.

Model 3: Contract Manufacturing (CMOs) - This is the fastest-growing part of the industry. Instead of selling their own drugs, companies like Egis Pharma Services and Patheon now manufacture for others. Brand-name companies outsource production. Smaller biotechs can’t afford their own plants. So they hire a CMO. This segment is projected to grow from $56.5 billion in 2025 to $90.9 billion by 2030. Why? Because it’s less risky. The CMO doesn’t own the brand. They don’t handle marketing. They just make the product. And they get paid upfront. Profit margins here are stable, often above 25%. For manufacturers stuck in the commodity trap, this is the escape route.

The Hidden Costs of Making Generics

If you think making a pill is simple, think again. The real cost isn’t the active ingredient. It’s everything else.Getting FDA approval for one generic drug (an ANDA) costs an average of $2.6 million. That’s not a one-time fee-it’s a multi-year process involving chemistry, stability testing, clinical bioequivalence studies, and inspections. And that’s just to get in the door.

Then there’s the factory. Building a compliant cGMP facility costs over $100 million. You need air filtration systems, sterile rooms, automated packaging lines, and quality control labs. And once you build it, you can’t just walk away. The FDA shows up unannounced. One violation, and you’re shut down for months.

Supply chain volatility adds another layer. Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) often come from India or China. A single political event or weather disruption can spike prices overnight. A manufacturer might lock in a price for a year, then wake up to a 30% increase. No one’s coming to rescue them. The market expects them to absorb it.

And here’s the kicker: it takes 18 to 24 months just to get your first product into formularies. Hospitals and insurers won’t switch to your drug unless you’ve proven reliability. That means you’re spending money for two years with zero revenue. Most startups fail before they even break even.

Global Divide: Who’s Winning?

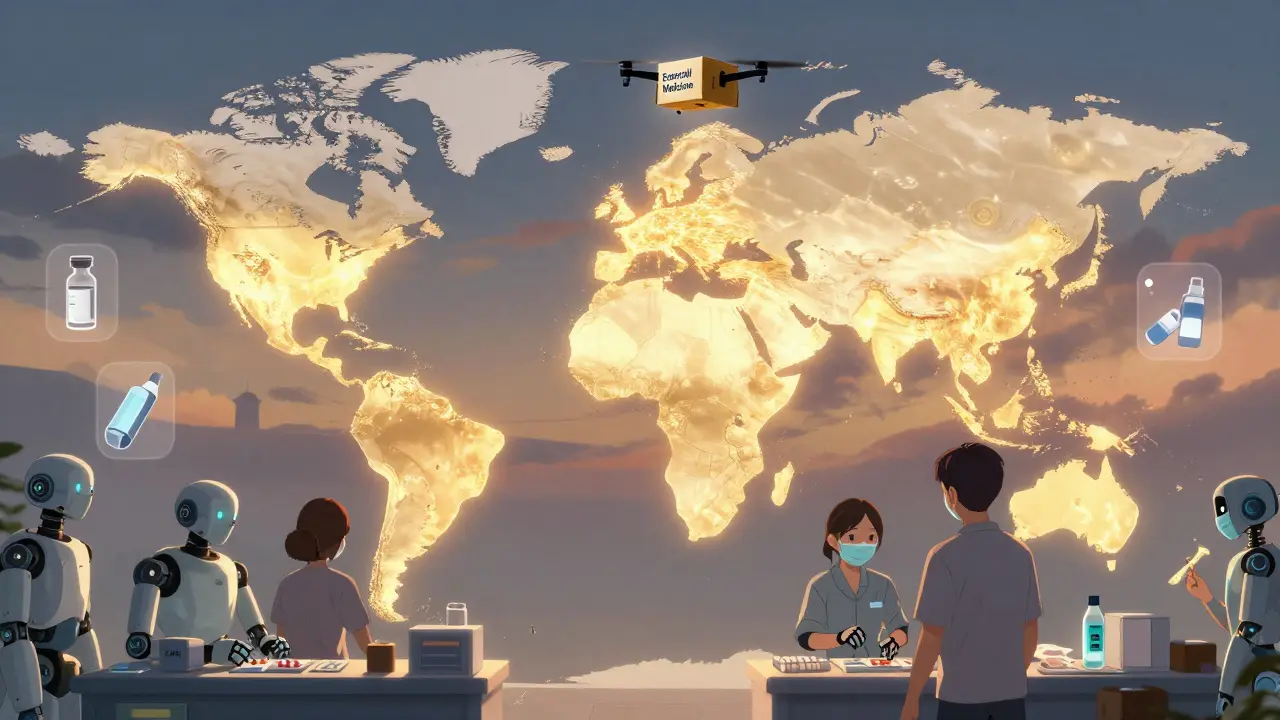

The U.S. market isn’t the whole story. Globally, the picture changes.In Europe, governments set drug prices. They don’t let PBMs run the show. That means less price slashing. Generic manufacturers there still make decent margins-sometimes over 30%. It’s not glamorous, but it’s steady.

In India and China, production costs are low. Many companies operate with margins under 15%, but they make up for it in volume. They’re not trying to compete in the U.S. They’re supplying lower-income markets. Their business model works because their cost structure is different.

The real opportunity? Emerging markets with rising healthcare demand. Nigeria, Indonesia, Brazil-places where people need affordable drugs and aren’t tied to U.S.-style PBM systems. These markets are growing fast. But they come with risks: currency swings, corruption, unreliable logistics. Only the most agile players can navigate them.

The Future: Innovation or Irrelevance?

The next decade will decide whether generic manufacturing survives as a pillar of public health-or becomes a relic of the past.On one side, there’s the looming wave of patent expirations. Dozens of blockbuster drugs-from Humira to Eliquis-are losing protection between 2025 and 2033. That’s a $600 billion opportunity. But will anyone be left to make them? Many manufacturers have already left the space. The ones that remain are either too small or too focused on low-margin products.

On the other side, there’s innovation. Companies that invest in complex delivery systems-like long-acting injectables, transdermal patches, or oral powders-are finding new life. Biosimilars, the generic version of biologic drugs, are another frontier. They’re not easy to make. But when you get it right, the margins are high and competition is limited.

Contract manufacturing is the quiet winner. It doesn’t need brand recognition. It doesn’t need marketing budgets. It just needs precision, reliability, and compliance. And that’s something you can build.

Why This Matters to You

You might not care about generic drug profits. But you care about whether your prescription is in stock. Whether your insulin costs $30 or $300. Whether your child’s asthma inhaler is available when they need it.When manufacturers can’t make money, they stop making drugs. And when they stop, people die. That’s not an exaggeration. Dr. Aaron Kesselheim of Harvard put it bluntly: “The relentless price competition in generics has created a market failure where essential medicines face shortages because manufacturers cannot profitably produce them.”

Healthcare systems want cheap drugs. But they also need them to be available. You can’t have one without the other. The system isn’t broken because manufacturers are greedy. It’s broken because the rules don’t allow them to survive.

Policy changes could help. Banning “pay-for-delay” deals-where brand companies pay generics to stay off the market-could save $45 billion over ten years. Strengthening price transparency. Rewarding manufacturers who keep production lines running during shortages. These aren’t radical ideas. They’re basic fixes.

The future of generic manufacturing isn’t about making more pills. It’s about making the right pills. The hard ones. The ones no one else can make. Or making them for others. The companies that adapt will survive. The ones that don’t? They’ll vanish. And with them, access to affordable medicine.

Why are generic drug prices falling so fast?

Prices are falling because of intense competition, especially in the U.S., where pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) force generic manufacturers into bidding wars. With dozens of companies making the same drug, the only way to win a contract is to undercut everyone else. This drives prices below production costs. Many manufacturers now sell at a loss, hoping to gain volume or market share-neither of which guarantees long-term survival.

What are complex generics, and why are they more profitable?

Complex generics are drugs that are hard to copy-like inhalers, injectables, or combination therapies. They require advanced formulation, specialized equipment, and deep regulatory knowledge. Fewer companies can make them, so competition is lower. That lets manufacturers charge higher prices. For example, a generic version of a complex cancer drug might have only 2-3 competitors, compared to 20+ for a simple tablet. Margins can reach 40-60%, compared to under 20% for commodity generics.

Can contract manufacturing save the generic drug industry?

Yes, for some. Contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) don’t compete on price-they compete on quality and reliability. They make drugs for brands, startups, and generics companies. This model has stable demand, predictable revenue, and margins above 25%. It’s less risky than owning a brand. Companies like Egis and Patheon are expanding rapidly. For manufacturers stuck in the commodity trap, shifting to CMO services is often the only way to stay in business.

Why do generic drug shortages happen?

Shortages occur when manufacturers stop producing a drug because they can’t make money. A drug with low margins, high production costs, or unreliable supply chains becomes unprofitable. When one company quits, others often follow. With no backup suppliers, shortages follow. This is especially common with older, low-cost drugs like antibiotics or injectables. The FDA estimates that over 100 drugs faced shortages in 2024 alone.

Is the global generic drug market growing?

Yes-but not everywhere. The U.S. generic market is shrinking due to pricing pressure. But globally, the market is projected to reach $600 billion by 2033. Growth is strongest in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, where healthcare access is expanding and regulatory systems don’t rely on U.S.-style PBMs. Countries like India and China are becoming major exporters of generics. The future of the industry lies outside North America.