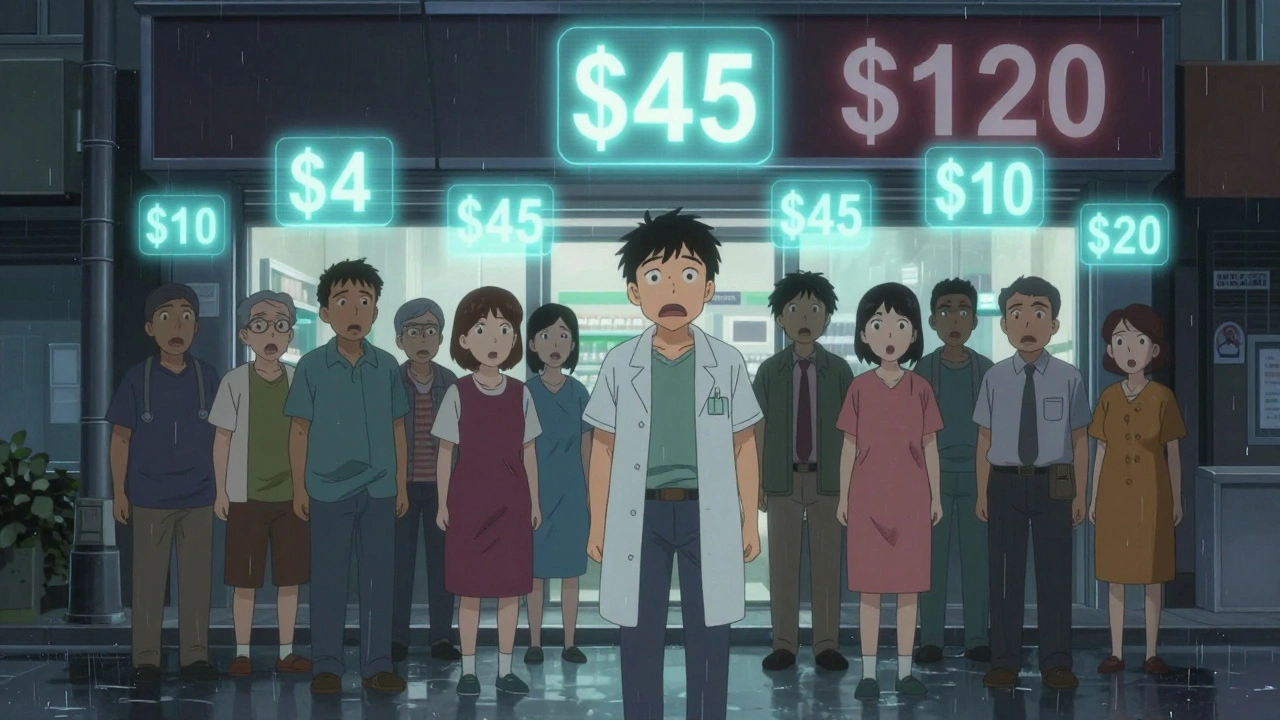

Ever bought a generic pill and been shocked by the price-only to find your neighbor paid a third of what you did for the exact same medicine? It’s not a mistake. It’s not fraud. It’s just how the system works. In the United States, the cost of a 30-day supply of generic atorvastatin, a common cholesterol drug, can swing from $4 in one state to over $120 in another. And it’s not just one drug. This pattern repeats across hundreds of generics, from metformin for diabetes to amoxicillin for infections. The reason? State-level differences in how drug prices are set, negotiated, and hidden.

How PBMs Control What You Pay

Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs, are the middlemen between drug manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacies. They’re supposed to negotiate lower prices. In reality, many act like secret brokers who profit from opacity. They strike deals with drugmakers that include rebates, but those rebates don’t always reach the consumer. Instead, they inflate the list price so insurers pay more-and you pay more out of pocket if your plan doesn’t cover the full cost. In states like California and New York, laws require PBMs to disclose how they set prices. That transparency means patients can shop around and often find better deals. But in states without those rules, PBMs can hide the real cost. A 2022 study from the USC Schaeffer Center found that consumers in states with weak PBM oversight paid 13% to 20% more for generics than those in states with stronger rules. And because most people don’t know their insurance isn’t getting the best price, they just pay what the pharmacy says.Medicaid and Reimbursement Rules

Medicaid, which covers over 80 million Americans, pays for most generic drugs using a benchmark called the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC). But not every state uses NADAC the same way. Some update it monthly. Others use a three-month average. Some cap reimbursements. Others don’t. That means a pharmacy in Ohio might get reimbursed $2.50 for a bottle of lisinopril, while one in Florida gets $4.20 for the same pill. That difference doesn’t just affect pharmacies-it affects you. If a pharmacy gets paid less, it may charge you more to make up the gap. Or it might not stock the drug at all. That’s why in rural areas of states like Mississippi or West Virginia, you might struggle to find certain generics-even if they’re widely available in urban areas of neighboring states.Competition (or Lack of It)

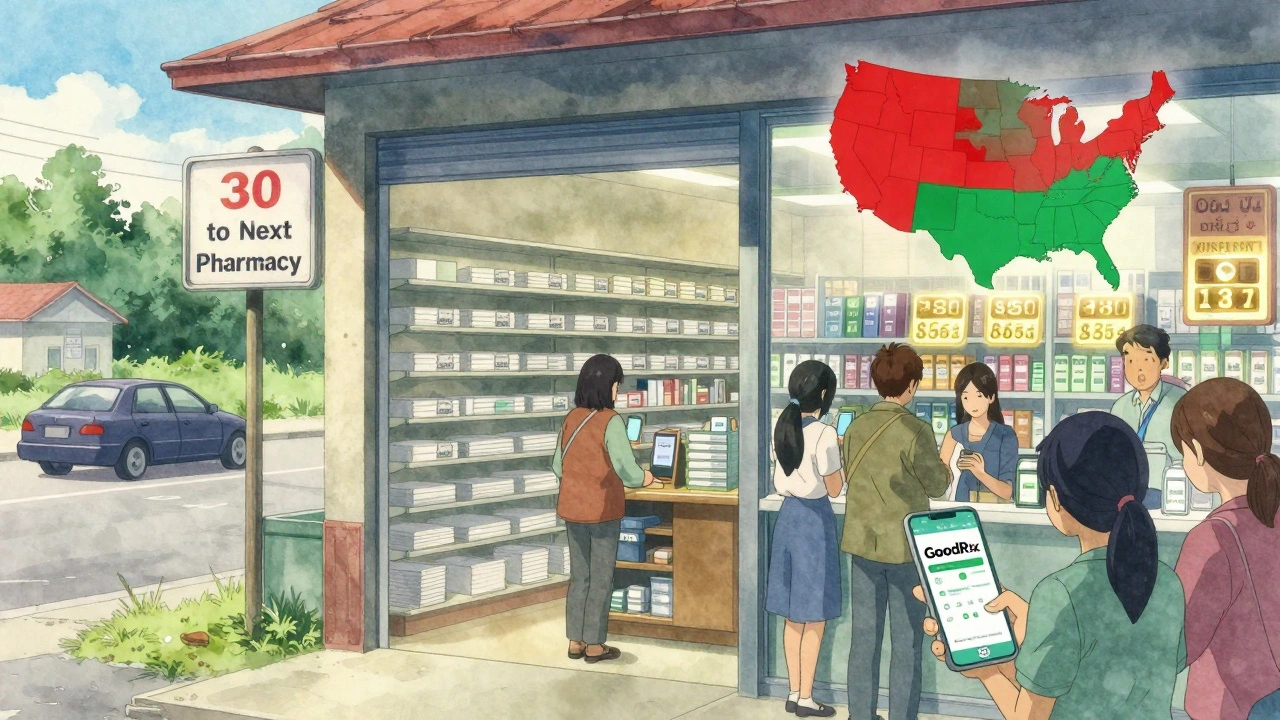

The more pharmacies in an area, the lower the price. Simple economics. But in many states, especially rural ones, there’s only one or two pharmacies within 30 miles. With no competition, they don’t need to lower prices. A 2022 GoodRx analysis showed that in some rural counties, the same generic drug cost 300% more than in a city just 50 miles away. Even in cities, consolidation matters. When one company owns multiple pharmacies-or when a PBM owns a pharmacy chain-it can set prices to maximize profit, not savings. That’s why cash prices at independent pharmacies are often cheaper than insurance prices at chain stores. In fact, 97% of cash payments for prescriptions are for generics, and those payments are often 30% to 70% lower than what insurance billed.

State Laws: The Good, the Bad, and the Blocked

Some states tried to fix this by passing laws to cap generic drug prices. Maryland did it in 2017, targeting price gouging on lifesaving generics. But a federal court shut it down, saying states can’t regulate interstate commerce. Nevada passed a similar law focused on diabetes drugs-but the lawsuit was dropped, likely because manufacturers threatened to sue under trade secrets laws. Still, 18 states have created drug affordability review boards as of 2023. These boards investigate price spikes and recommend actions. They can’t set prices, but they can shame companies into lowering them. California’s transparency law requires PBMs to report their pricing formulas. The result? Patients there pay 8% to 12% less on average for generics than those in states without similar laws.Why Paying Cash Beats Insurance (Sometimes)

If you’re paying for a generic drug out of pocket, you’re often better off skipping insurance entirely. Why? Because insurers and PBMs have complex contracts that inflate prices. Your copay might look low, but your insurer is paying far more behind the scenes-and that cost gets passed on to you through higher premiums and deductibles. Services like GoodRx, Blink Health, and Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company let you compare cash prices across pharmacies. In many cases, you’ll pay less than your insurance copay. For example, a 90-day supply of generic atorvastatin might cost $45 with insurance in California, but only $12 cash at a local pharmacy using GoodRx. In Texas, the same drug might cost $120 with insurance-but $15 cash. That’s not a typo. It’s the system working as designed: profit first, patient second.

The Inflation Reduction Act Isn’t Enough

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act capped insulin at $35 a month for Medicare patients and limits out-of-pocket drug spending to $2,000 a year starting in 2025. That’s huge-for the 32% of Americans on Medicare. But it does nothing for the 68% who aren’t. And even for Medicare patients, the savings depend on your state. If your state has weak PBM rules, your pharmacy might still charge more than the cap. The cap applies to what Medicare pays, not what the pharmacy charges. So if your pharmacy inflates the price, you could still end up paying more.What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for lawmakers to fix this. Here’s how to pay less today:- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices before you fill your prescription.

- Ask your pharmacist: "What’s the cash price?" Always. It’s not rude-it’s smart.

- If your cash price is lower than your copay, pay cash. Tell your insurer you’re opting out.

- Check if your state has a drug affordability board. Look up your state health department’s website.

- Consider mail-order pharmacies or direct-purchase services like Cost Plus Drug Company if you take the same meds every month.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for just 18% of total drug spending. That’s because prices are artificially high-not because of manufacturing costs, but because of hidden fees, secret rebates, and weak oversight. The problem isn’t the pills. It’s the system. States are trying to fix it. But without federal coordination, progress is uneven. In the meantime, the burden falls on you. The good news? You have more power than you think. By asking the right questions and using cash-price tools, you can cut your generic drug costs by half-or more-no matter where you live.Why is my generic drug so much more expensive than my friend’s in another state?

Because each state has different rules for how pharmacies and insurance companies set prices. PBMs, Medicaid reimbursement rates, and pharmacy competition vary widely. Your friend might be paying cash, or their state has stronger transparency laws that keep prices lower.

Should I always use my insurance to pay for generics?

No. Many times, the cash price is lower than your insurance copay. This happens because insurers and PBMs have complex contracts that inflate the billed price. Always ask your pharmacist for the cash price before using insurance.

Are generic drugs the same everywhere?

Yes. The FDA requires all generic drugs to meet the same standards for safety, strength, and effectiveness as brand-name drugs. The difference isn’t in the medicine-it’s in the pricing system.

Can my state cap the price of generic drugs?

Not directly. A federal court blocked Maryland’s law because it interfered with interstate commerce. But 18 states have created affordability review boards that can investigate and recommend price actions. They can’t set caps, but they can pressure companies to lower prices.

Why do rural pharmacies charge more for generics?

Fewer pharmacies mean less competition. Without rivals, a pharmacy can charge more and still keep customers. Rural areas also have higher operating costs and fewer bulk-buying options, which gets passed on to patients.

Does the Inflation Reduction Act help with generic drug prices?

Only for Medicare patients. It caps insulin at $35 and limits out-of-pocket spending to $2,000 a year starting in 2025. But for people under 65 or not on Medicare, it doesn’t change how generics are priced in your state.

How can I find out if my state has drug pricing transparency laws?

Visit your state’s department of health website and search for "drug pricing transparency" or "pharmacy benefit manager regulation." States like California, New York, and Vermont have strong laws. Others have none.