When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way-no matter how identical the pills look? For many people, the difference isn’t in the ingredients. It’s in their genes.

Why Your Family’s Medical History Matters More Than You Think

Your family’s health history isn’t just about who had heart disease or diabetes. It’s also about who got sick from a common painkiller, who needed a lower dose of blood thinner, or who had a bad reaction to an antidepressant. These aren’t random accidents. They’re often clues written in your DNA.Take warfarin, a blood thinner used to prevent clots. Some people need 5 mg a day. Others need 15 mg. Why? Because of variations in two genes: CYP2C9 and VKORC1. If your parent had a dangerous bleed on warfarin, you might carry the same genetic variant. A generic version of warfarin is chemically identical to the brand name-but if your body can’t process it properly, the risk doesn’t go away.

Studies show that genetic differences explain 20% to 95% of how people respond to medications. That’s not a small range. It’s the difference between a drug saving your life and nearly killing you.

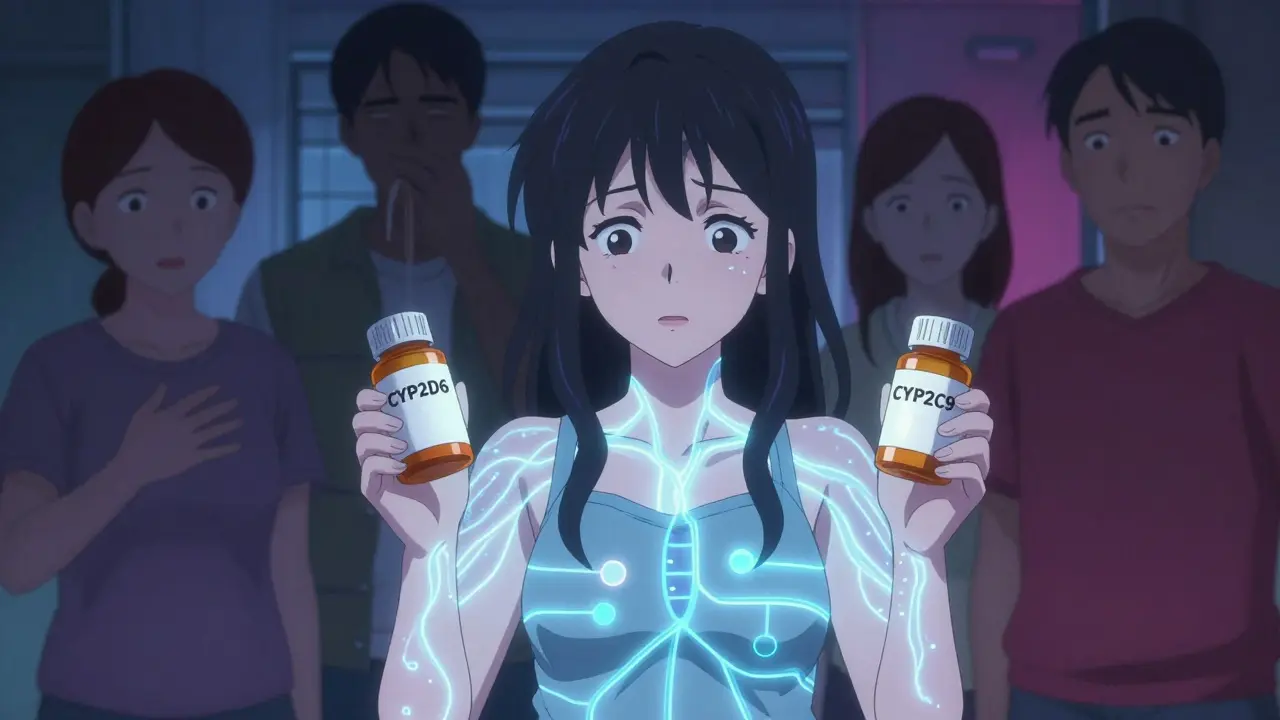

How Your Genes Break Down Medications

Your liver has a team of enzymes that break down drugs. The most important group? The cytochrome P450 enzymes. The CYP2D6 gene alone affects how your body processes about 25% of all prescription drugs-antidepressants, painkillers, beta-blockers, even some asthma inhalers.There are over 80 known variants of CYP2D6. Some make you a fast metabolizer: your body clears the drug too quickly, so it doesn’t work. Others make you a poor metabolizer: the drug builds up in your system, causing side effects like dizziness, nausea, or even serotonin syndrome.

One real case from a patient in Auckland: After switching from a brand-name antidepressant to its generic, they developed severe anxiety and shaking. Their doctor dismissed it as "adjustment." But after a genetic test, they found they were a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. The generic had the same active ingredient-but without knowing their genetics, the dose was still too high for their body.

Other genes matter too:

- CYP2C9: Affects warfarin, ibuprofen, and some diabetes drugs. Variants here mean you need much lower doses.

- TPMT: If you have low activity, standard doses of azathioprine (used for autoimmune diseases) can wipe out your white blood cells.

- DPYD: If you’re missing this enzyme, 5-fluorouracil (a chemo drug) can poison you. Dose reduction isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

These aren’t rare. In fact, about 1 in 10 people of European descent are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6. In Asian populations, that number jumps to 1 in 5 for CYP2C19-affecting proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole.

Why Generics Can Still Be Risky-Even When They’re "Identical"

Generic drugs must meet strict standards for bioequivalence. That means they release the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream as the brand name, within a narrow range.But here’s the catch: bioequivalence doesn’t care about how your body processes that drug. Two people can take the same generic pill. One breaks it down fine. The other can’t. The pill doesn’t change. Your genes do.

That’s why switching to a generic isn’t always safe if you’ve had bad reactions before. A patient who had a severe reaction to a brand-name statin might assume the generic is fine. But if their HMGCR gene variant reduces statin effectiveness, the generic won’t help-and they won’t know why their cholesterol stays high.

And it’s not just about side effects. Sometimes, the drug just doesn’t work. A 2024 study found that people with certain genetic variants in the SLC22A1 gene had worse responses to metformin, a common diabetes drug. The generic version? Same result. Same failure. Same unexplained high blood sugar.

Population Differences You Can’t Ignore

Genetic variants aren’t spread evenly across the world. What’s common in one group can be rare in another.For example:

- 15-20% of East Asian populations are poor metabolizers of CYP2C19. That means proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole won’t work well for them-and they may need a different drug entirely.

- African ancestry populations often need higher warfarin doses due to genetic differences in VKORC1 and CYP2C9. But if a doctor uses a "one-size-fits-all" dosing chart based on European data, they’re setting up a patient for a clot-or a bleed.

- The rs3846662 variant in the HMGCR gene (linked to poor statin response) is far more common in Sub-Saharan African populations than in Europeans.

That’s why blanket recommendations based on ethnicity or ancestry can be misleading. A doctor in New Zealand prescribing a generic drug to someone with Māori, Pacific Islander, or South Asian heritage might be missing key genetic signals that affect drug metabolism.

What You Can Do-Before You Switch

You don’t need to wait for a bad reaction. Here’s what works:- Ask about your family’s drug history. Did anyone in your family have a severe reaction to a common medication? Write it down.

- Ask your doctor if pharmacogenetic testing is right for you. Especially if you’ve had bad side effects, multiple failed treatments, or you’re on a drug with known genetic links (like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antidepressants).

- Don’t assume generics are risk-free. If you’ve had a reaction before, the generic might be the same problem under a different label.

- Know your genes if you can. Tests like Color Genomics or OneOme cost around $250 and screen for 10-15 key genes. Some health systems in New Zealand are starting to offer these for high-risk patients.

A 2023 Mayo Clinic study followed 10,000 people who got preemptive genetic testing. 42% had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. Two-thirds of those cases led to a medication change-and adverse events dropped by 34%.

The Big Hurdle: Doctors Don’t Always Know What to Do

Even when you get tested, the results don’t always get used. A 2022 survey of 1,247 clinicians found that 79% said they didn’t have enough time to interpret genetic results. Only 32% felt confident using HLA-B*15:02 results to avoid carbamazepine reactions.Some doctors still think pharmacogenetics is "experimental." But over 300 drug labels in the U.S. now include genetic information. The FDA recommends it for warfarin. CPIC (Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium) has published 24 guidelines for doctors-covering 41 drugs.

The problem isn’t the science. It’s the system. Electronic health records rarely flag genetic risks. Prescribing software doesn’t auto-adjust doses based on CYP2D6 status. Most GPs in New Zealand still don’t have decision support tools built in.

What’s Changing-And What’s Next

Things are moving. The NIH spent $127 million on pharmacogenomics research in 2023-with a focus on underrepresented groups. The All of Us program aims to return genetic results to 1 million Americans by 2026. In New Zealand, the public health system is starting pilot programs for pharmacogenetic testing in mental health and cardiology.Future tools will use polygenic scores-looking at hundreds of genes at once-to predict drug response with 68% accuracy, far better than single-gene tests.

But right now, the most powerful tool you have is your own history. If your mother had a bad reaction to a generic painkiller, if your father needed three different antidepressants before one worked, if your sibling had to stop chemotherapy because of toxicity-those aren’t just stories. They’re red flags written in your genes.

Don’t assume a generic is safe just because it’s cheaper. Ask questions. Share your family history. Push for testing if you’ve had bad experiences. Your genes don’t change. But your care can-if you speak up.

Can family history really predict how I’ll react to a generic drug?

Yes. If close relatives had severe side effects, poor response, or unexpected reactions to medications-especially those metabolized by liver enzymes like CYP2D6 or CYP2C9-your genes may be similar. Family history is often the first clue that genetic testing could help.

Are generic drugs less effective because of genetics?

No. Generics contain the same active ingredient as brand-name drugs. But if your body can’t process that ingredient properly due to your genes, the drug won’t work as intended-whether it’s generic or brand. The problem isn’t the pill. It’s your metabolism.

What should I do if I’ve had a bad reaction to a generic drug?

Don’t assume it was just bad luck. Document the reaction, the drug name, and the dose. Ask your doctor for a pharmacogenetic test, especially if you’re on long-term medication. Tests for CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and TPMT are the most clinically useful right now.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance in New Zealand?

Currently, most pharmacogenetic tests are not covered by public health funding unless you’re in a clinical trial or have a high-risk condition like cancer or severe depression. Some private insurers and workplace health programs may cover them. Tests from companies like Color Genomics cost around $249.

Can I get tested before switching to a generic?

Absolutely. Preemptive testing-getting tested before you even start a new drug-is becoming more common in hospitals. If you’re on multiple medications or have a complex medical history, asking for testing before a switch can prevent dangerous side effects.

What to Do Next

If you’re considering switching to a generic drug:- Review your family’s medication history-especially reactions.

- Ask your GP or pharmacist: "Is this drug affected by genetics?"

- If you’ve had bad reactions before, request a pharmacogenetic test.

- Don’t accept "it’s just a generic" as an answer if something feels off.

- Use resources like PharmGKB or CPIC guidelines (available online) to understand your results.

Medicine is no longer one-size-fits-all. Your genes are part of your medical identity. Ignoring them when switching to generics isn’t cost-saving-it’s risky. And in a world where 34% fewer adverse events are possible with testing, that’s a risk you don’t have to take.