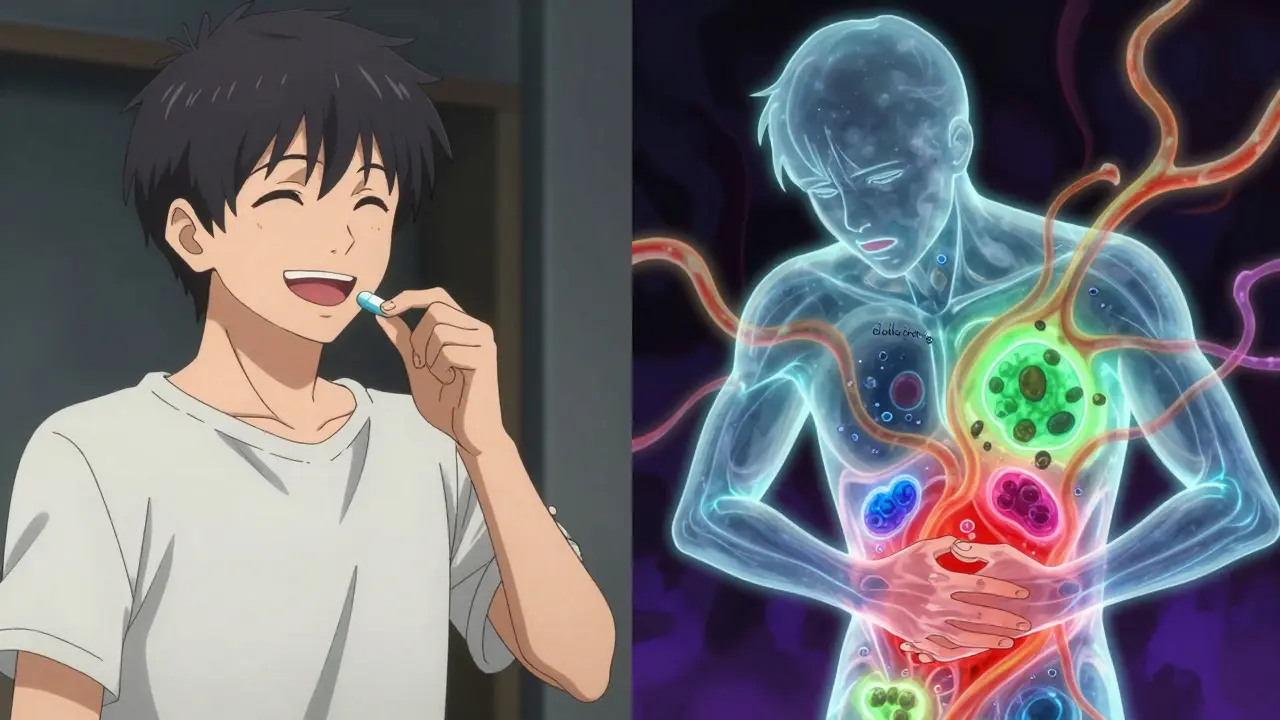

Most people assume that if a generic drug has the same active ingredient as the brand-name version, it’s exactly the same. But that’s not true - and the difference could matter more than you think. While the medicine inside the pill works the same way, what’s on the outside - the fillers, dyes, preservatives, and binders - can vary wildly. And for some people, those invisible ingredients are the reason they feel worse after switching to a cheaper version.

What Are Inactive Ingredients, Really?

Inactive ingredients, also called excipients, are the non-medicinal parts of a pill. They don’t treat your condition. But they do everything else: hold the pill together, help it dissolve at the right time, make it easier to swallow, or even give it color. In many pills, more than half the weight isn’t medicine at all. Some tablets are over 99% inactive ingredients. That’s not a typo - it’s standard practice. These ingredients are approved by the FDA as safe for most people. But safety for the majority doesn’t mean safety for everyone. Lactose, gluten, peanut oil, artificial dyes, and FODMAP sugars are common in generics. If you’re lactose intolerant, allergic to peanuts, or have IBS, you might be swallowing triggers without knowing it.Why Generic Medications Can Be Different

Generic drug makers don’t have to copy the brand-name pill exactly. They just need to prove their version delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream within an acceptable range. That’s called bioequivalence. But there’s no rule saying they must use the same fillers. That means two different generic versions of the same drug - say, levothyroxine - could have completely different inactive ingredients. One might use corn starch. Another might use lactose. A third might use a dye that causes skin reactions in sensitive people. And you won’t know unless you check. This isn’t a flaw in the system. It’s how the system works. The FDA allows this flexibility because it encourages competition and lowers prices. But for patients with allergies, sensitivities, or chronic conditions, that flexibility can become a problem.Real Problems, Real Stories

People aren’t imagining this. There are hundreds of reports online and in medical databases of side effects that started after switching to a generic. One patient on Reddit switched from Synthroid to generic levothyroxine and developed severe stomach cramps. The symptoms vanished when she went back to the brand. Another person reported a rash after switching to a generic version of a blood pressure pill - a reaction that never happened before. A 2022 survey by MedShadow found that 27% of people who switched to generics experienced new side effects. Of those, 68% blamed the inactive ingredients. These aren’t rare cases. They’re common enough that doctors in New Zealand and the U.S. are starting to ask patients: “Did you recently switch meds?” Even the FDA admits that while most people won’t notice a difference, “a small subset of patients may experience adverse effects” due to changes in excipients. That’s why they recommend talking to your doctor if you feel worse after switching.

Which Inactive Ingredients Should You Watch For?

Not all fillers are equal. Some are harmless for almost everyone. Others are red flags for specific groups:- Lactose - Found in about 20% of all oral medications. Can cause bloating, gas, and diarrhea in people with lactose intolerance.

- Gluten - Not always labeled. Can trigger reactions in people with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

- FODMAP sugars - Like lactose, fructose, or sorbitol. Trigger IBS symptoms in up to 55% of medications.

- Bisulfites - Used as preservatives. Can cause asthma attacks in sensitive individuals. These are required to be labeled - but many other allergens aren’t.

- Artificial dyes - Red 40, Yellow 5, Blue 1. Linked to skin rashes and hyperactivity in children.

- Peanut oil - Rare, but used in some liquid medications. Always labeled, but easy to miss.

How to Find Out What’s in Your Pill

You can’t rely on the pharmacist to know off the top of their head. You need to check the official source. Start with the Drug Facts sheet that comes with your medication. It’s often tucked inside the box. Look for the section labeled “Inactive Ingredients.” That’s your goldmine. If you don’t have it, go to the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database. Search by the drug name and strength. You’ll see every excipient approved for that formulation. But be warned - it’s technical. It lists chemical names, not common ones. “Lactose monohydrate” isn’t labeled as “milk sugar.” Your best move? Ask your pharmacist to check the manufacturer’s product information. Most pharmacies can pull up the exact formulation used for the batch they’re dispensing. If you’re sensitive to something, ask: “Can you confirm this version doesn’t have [lactose/gluten/dye]?”